New River Folk

A fictional museum of working-class water culture by Laura Copsey and Philip Crewe

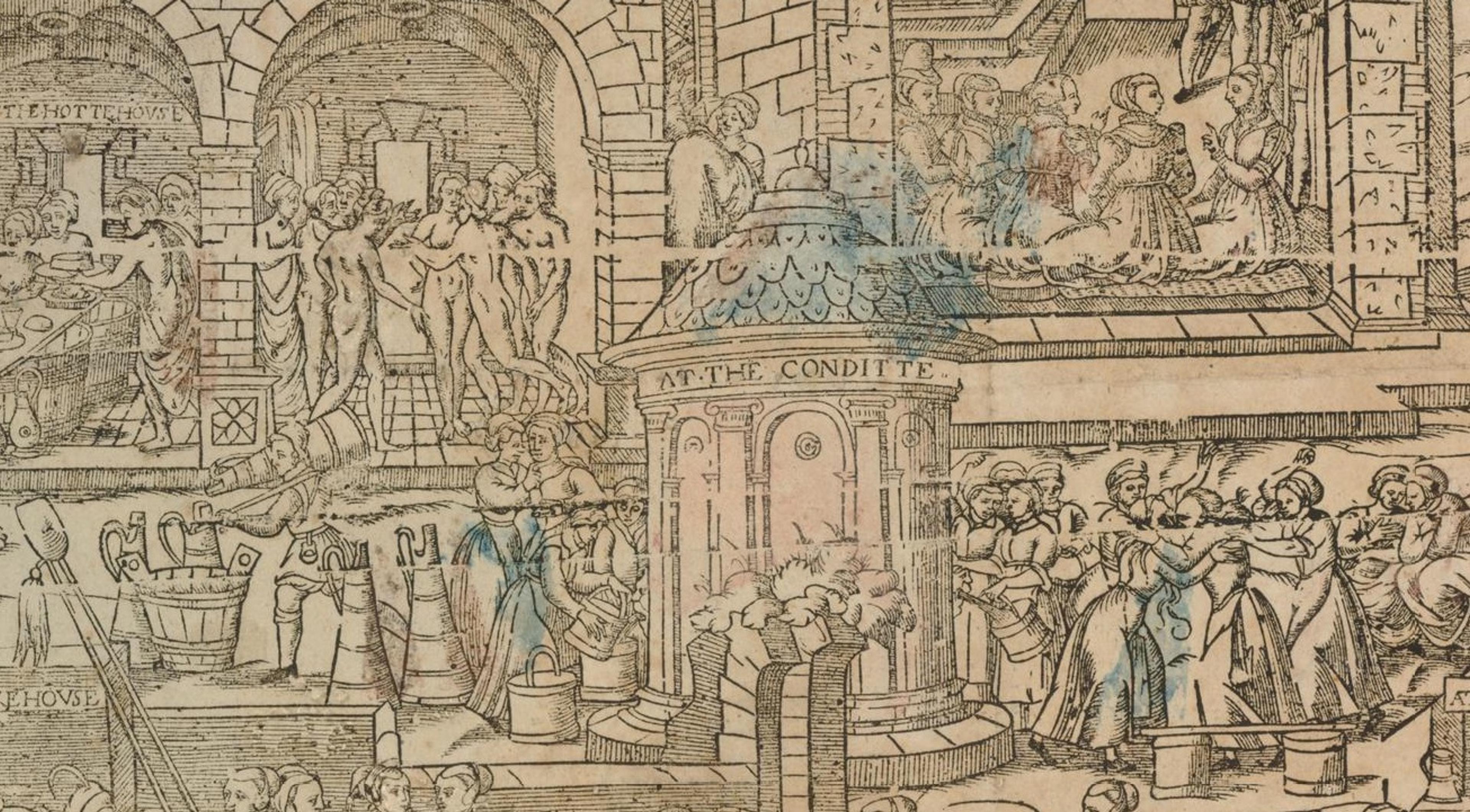

New River Head in Clerkenwell is part of a historic landscape of water that included wells, spas, springs and rivers. At the time of the New River’s construction in 1604, water was seen by many people as sacred. Water-related rituals and superstitious beliefs were an important part of life.

Once completed in 1613, the New River created a major shift in people’s relationship with water. The river was an engineering feat that brought much-needed, ‘sweete’ fresh water to London. At the same time, it replaced medieval water culture in the city. People no longer gathered at communal wells and fountains. This weakened social bonds and the potential for collective political action. It moved people away from nature and increased their reliance on technology and infrastructure.

Below are objects attributed to three Londoners who were affected by this change. Mary Woolaston (a well-keeper), Joan Starkey (a tankard-bearer) and William Mollitrape (a mole catcher employed by the New River Company). They are part of the New River Folk museum’s collection and were excavated by narrative archaeologists Copsey and Crewe in 2021.

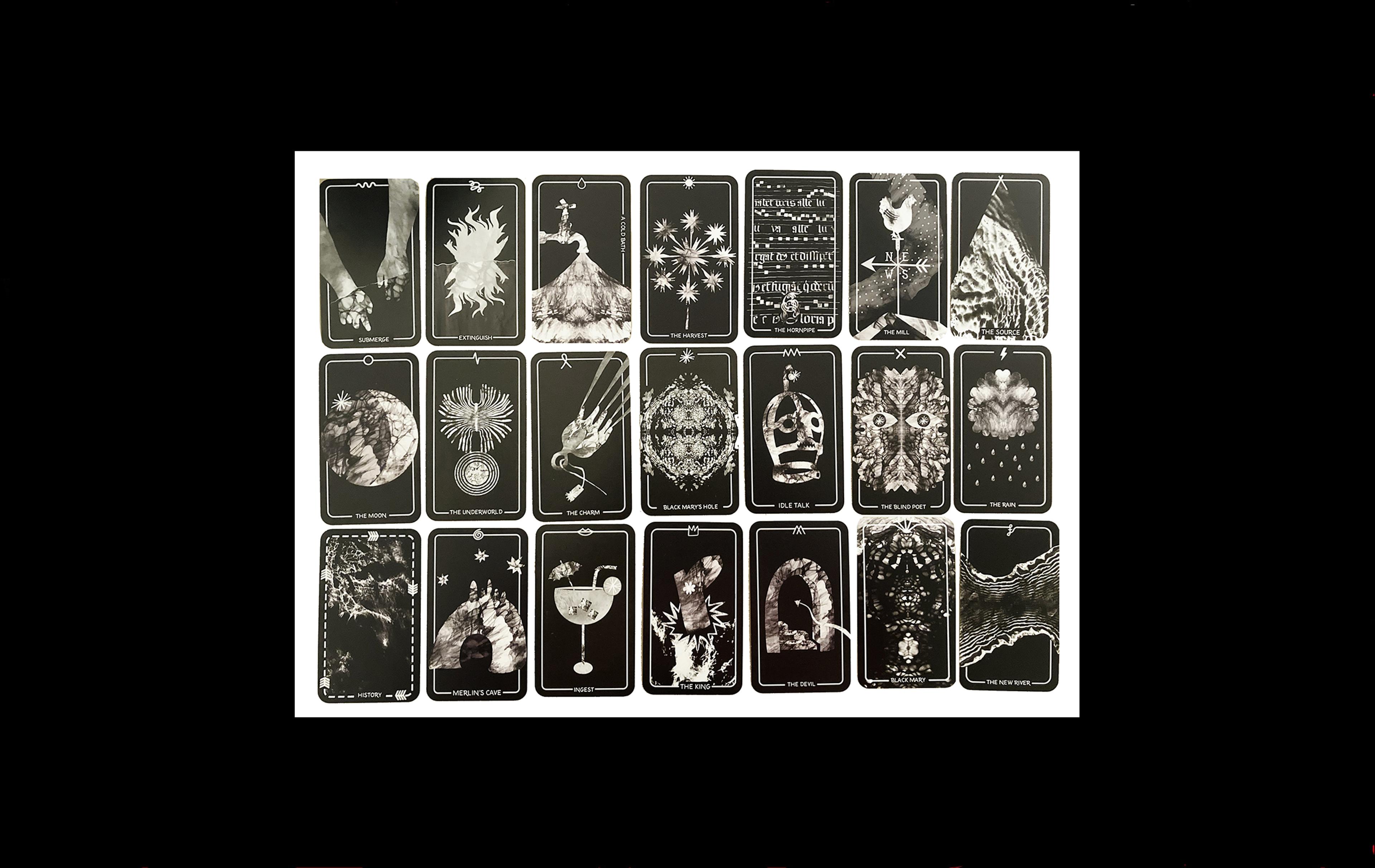

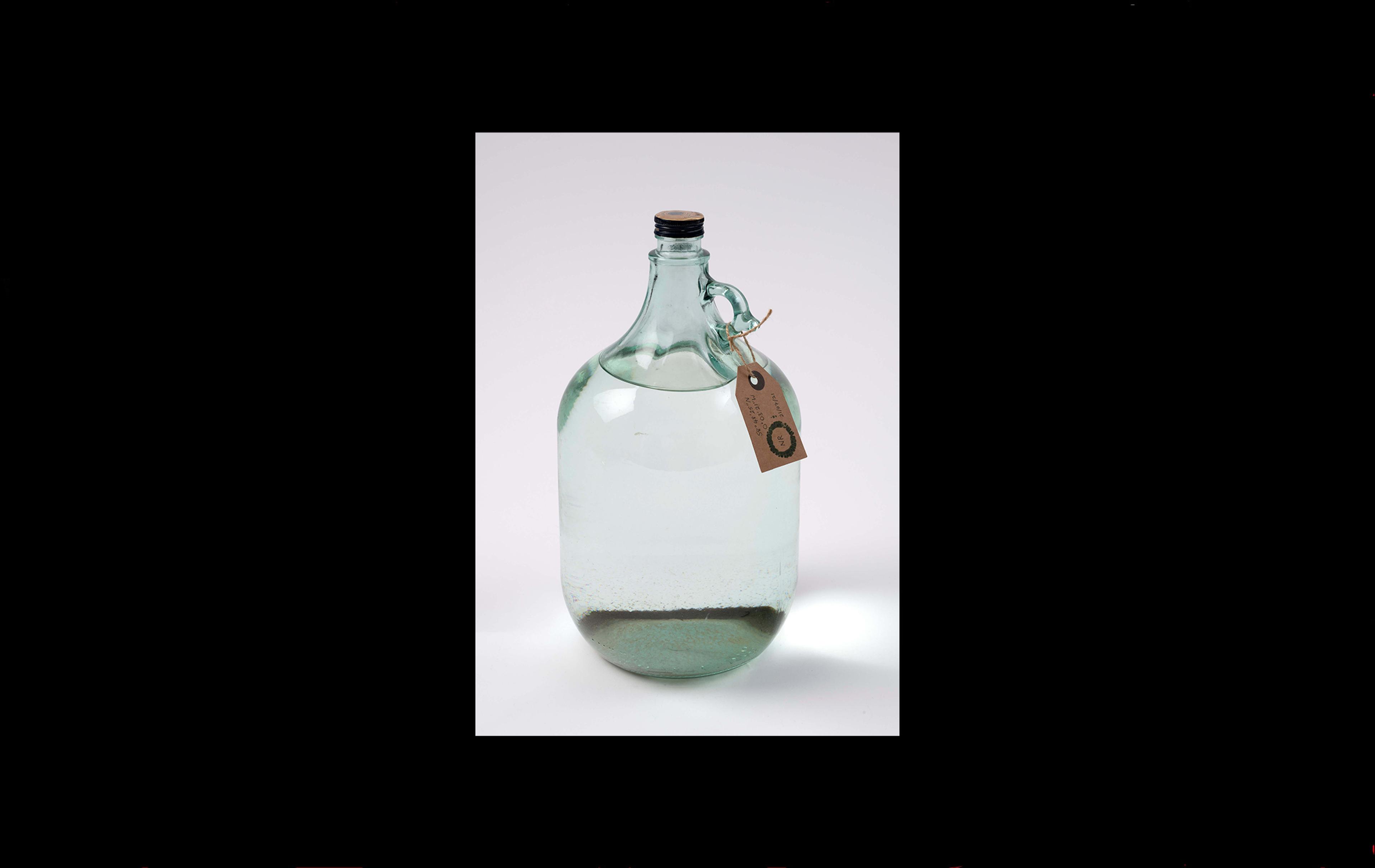

Mary Woolaston (Black Mary), well-keeper

The River Fleet in London was once called the River of Wells and Black Mary’s Hole was one of them. It was located close to Sadler’s Well.

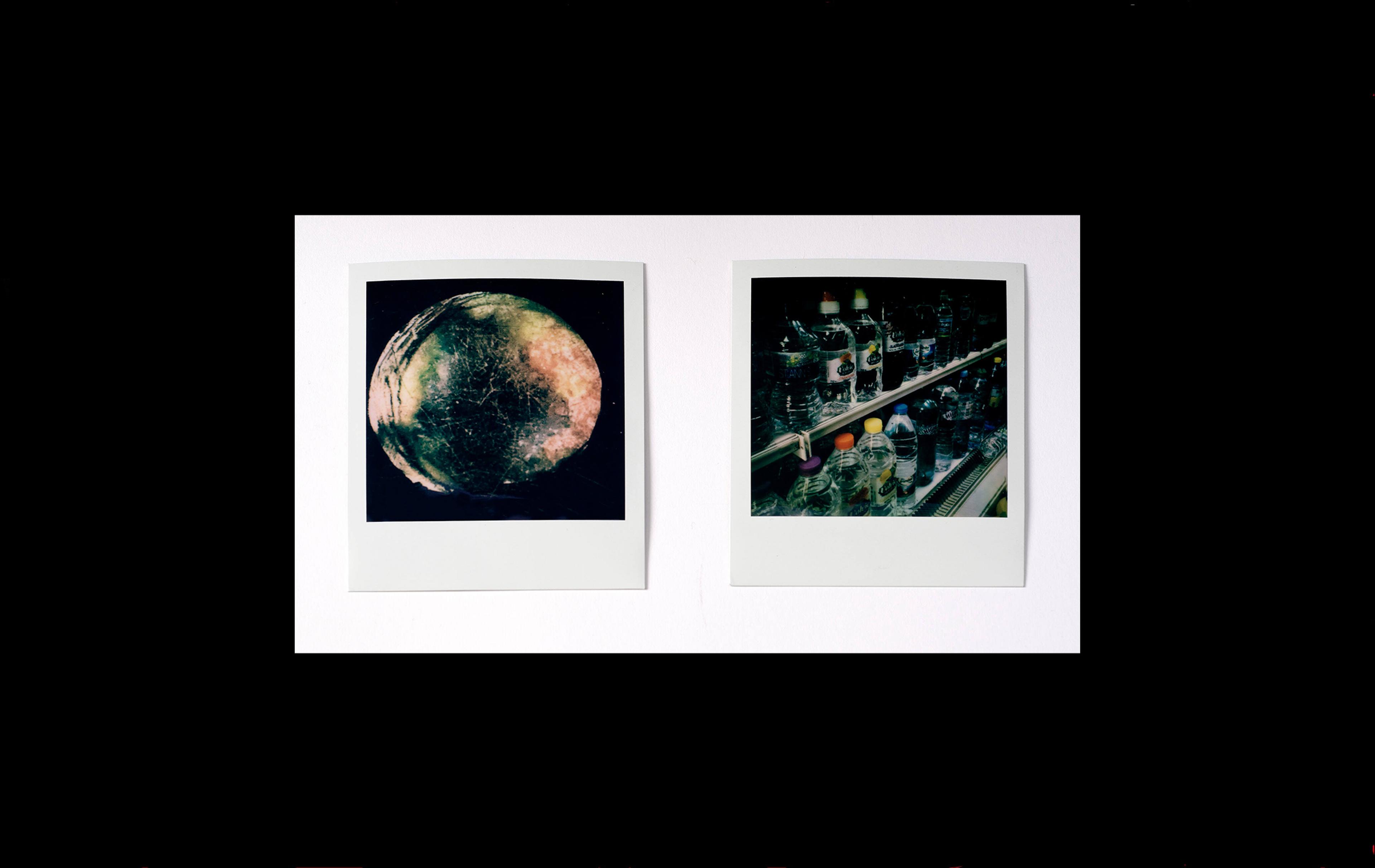

In medieval culture, ‘miracle plays’ based on biblical themes were regularly performed at wells. But Black Mary’s Hole was said to be for the more mystic customer. Guests would visit on a full moon for ritual and the water’s healing properties – especially the ability to cure sore eyes.

There are many theories about the origin of the name ‘Black Mary’s Hole’. One curious account from 1813 says that “the hole, was leased to one Mary Woolaston, who kept a black cow, whose milk the gentleman and ladies consume, with the conduit waters.” Recent research suggests that Black Mary may have been a woman of colour making a living from the sale of healing waters. Or was Black Mary a nun from nearby St Mary’s Priory, dressed in a black habit?

In 2006 a local psychic visited the vicinity of Black Mary’s Hole. They said the hole was a sacrificial pit dedicated to a lunar goddess. Is it a coincidence lunar deities such as Isis and Hathor are often portrayed as cows?

No trace of Black Mary’s Hole survives today. It has been built over and perhaps now rests under the housing block named Spring House on Cubitt Street.

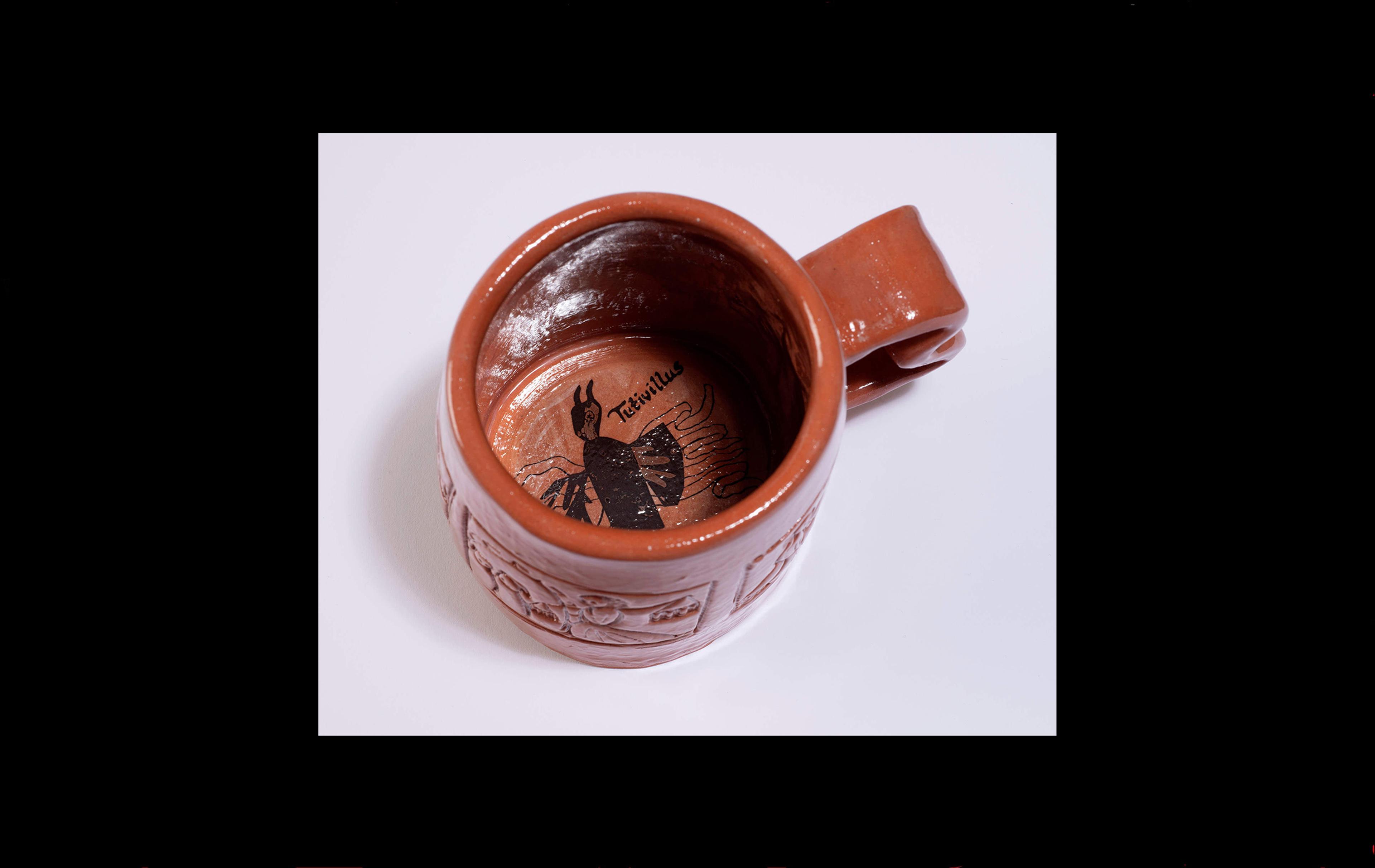

Joan Starkeye, tankard-bearer

Water tankard-bearers were a large union of low-status workers, often women and children. They earned a living by collecting free water and selling it door-to-door by the tankard. Joan Starkeye was one of this collective, sourcing water each day from whichever of the quarrelsome wells was least polluted.

The arrival of the New River Company’s profit-making piped water service put many tankard-bearers out of work. This presented a moral question for wealthier citizens who saw hiring tankard-bearers as a charitable act.

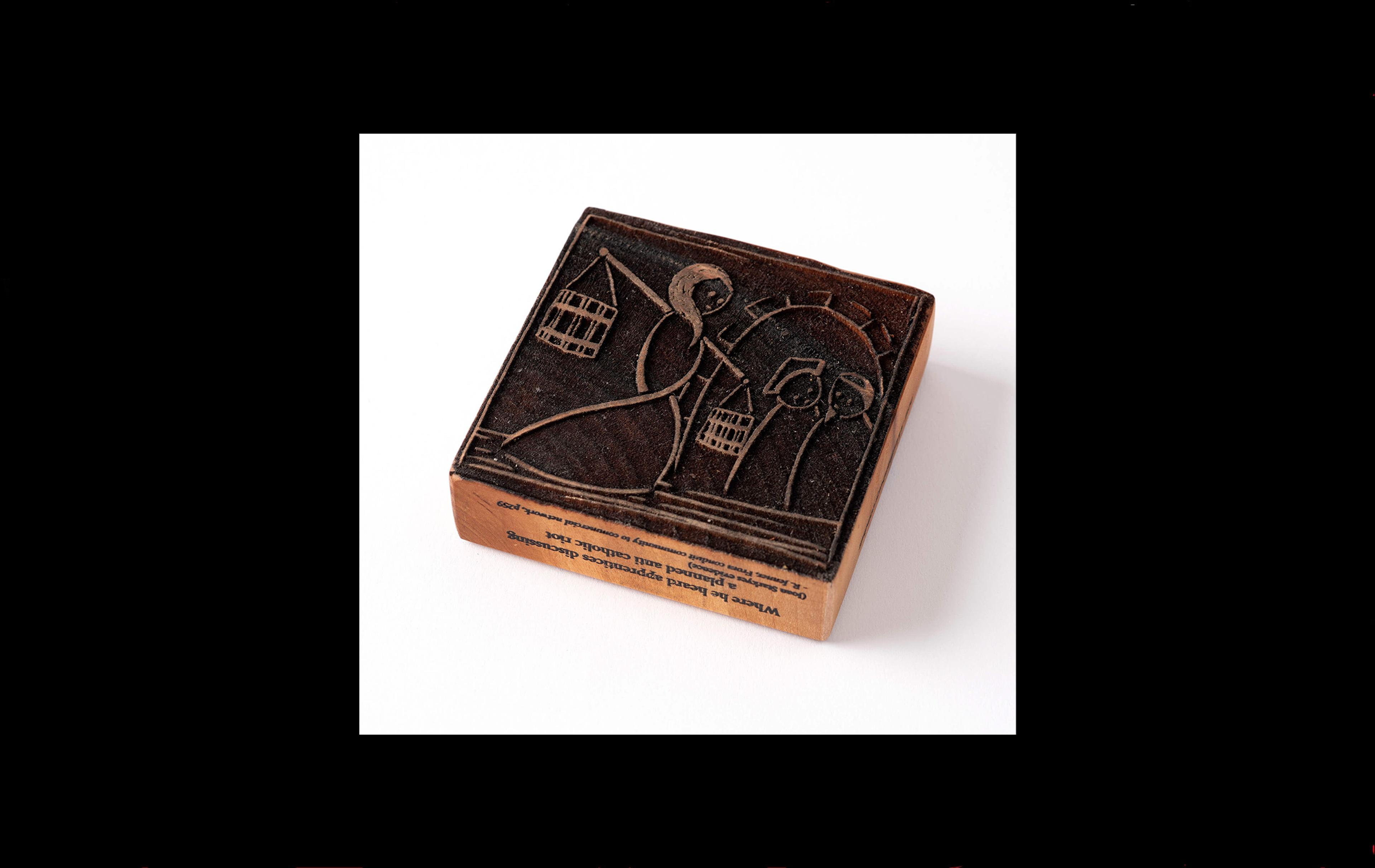

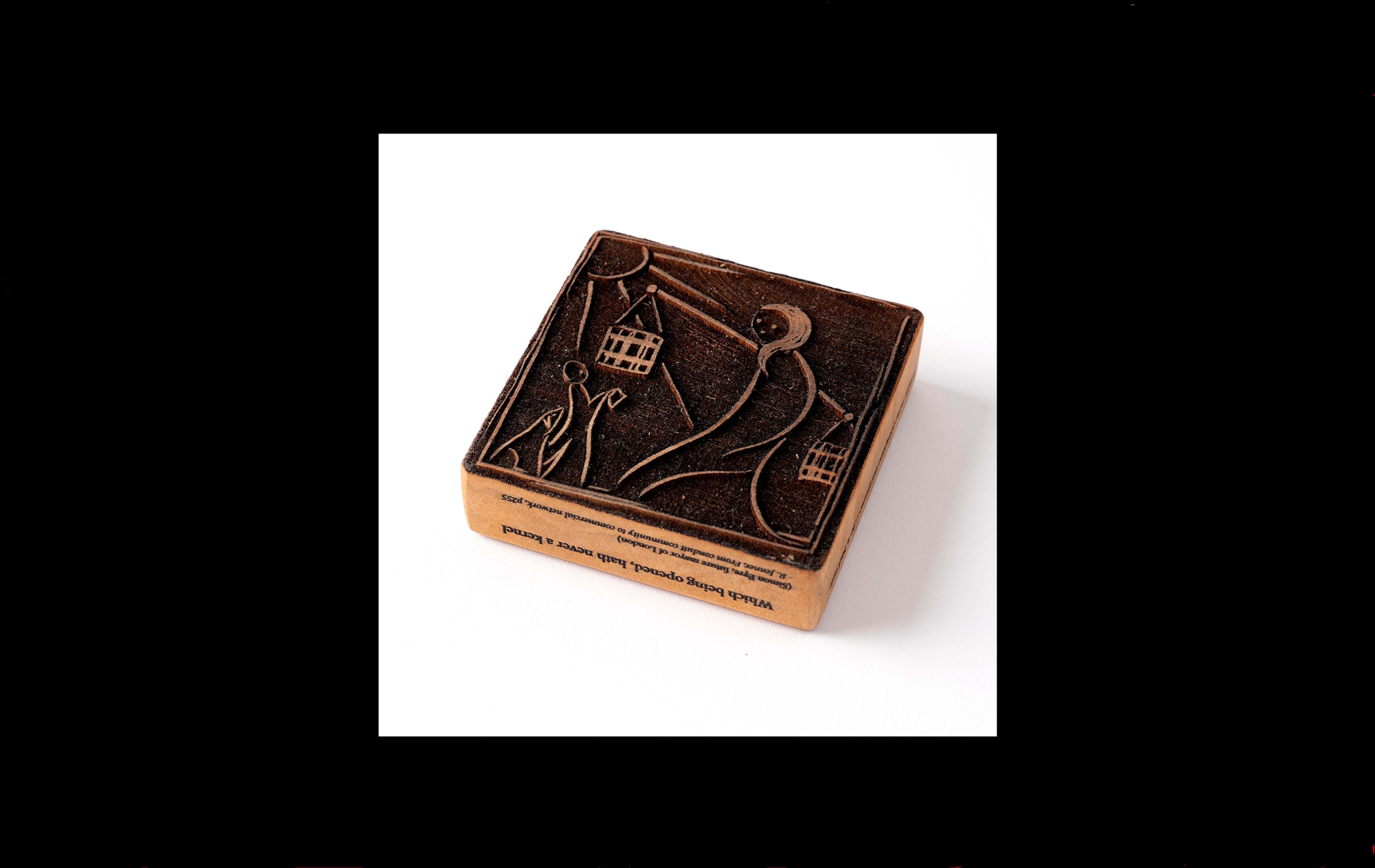

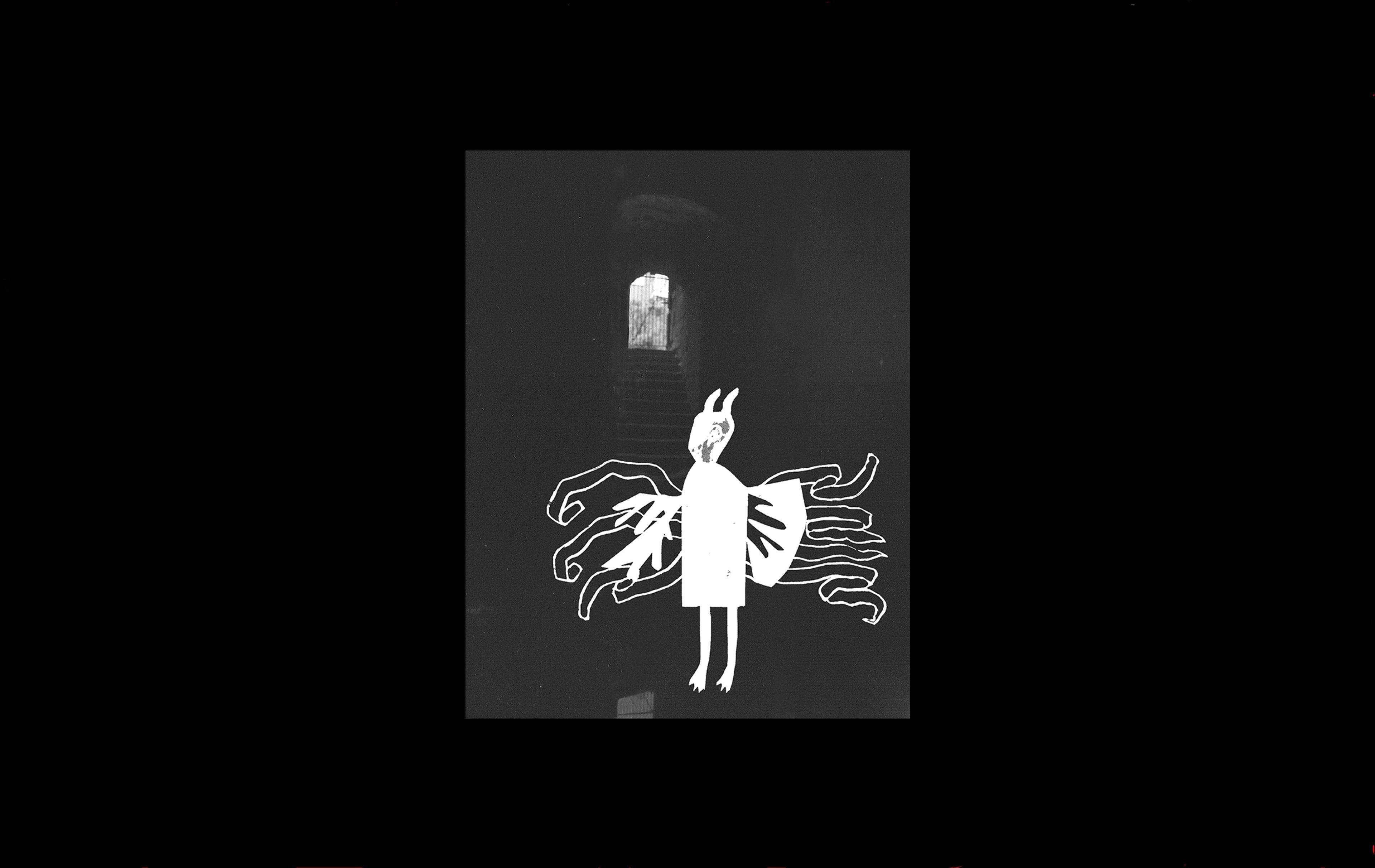

Joan and others like her would have been privy to local gossip that was shared at communal wells and fountains. In the medieval era this was frowned upon. The Church said that a demon called Tutivillus would write the name of anyone engaging in ‘idle talk’ on a long scroll to be read on Judgement Day.

The idea of ‘idle talk’ was used as a method of control, a tactic to silence ‘disobedient’ women. Joan may have been vulnerable to accusations of idle talk, a punishable sin where the accused may have to wear a scold’s bridle, a kind of muzzle.

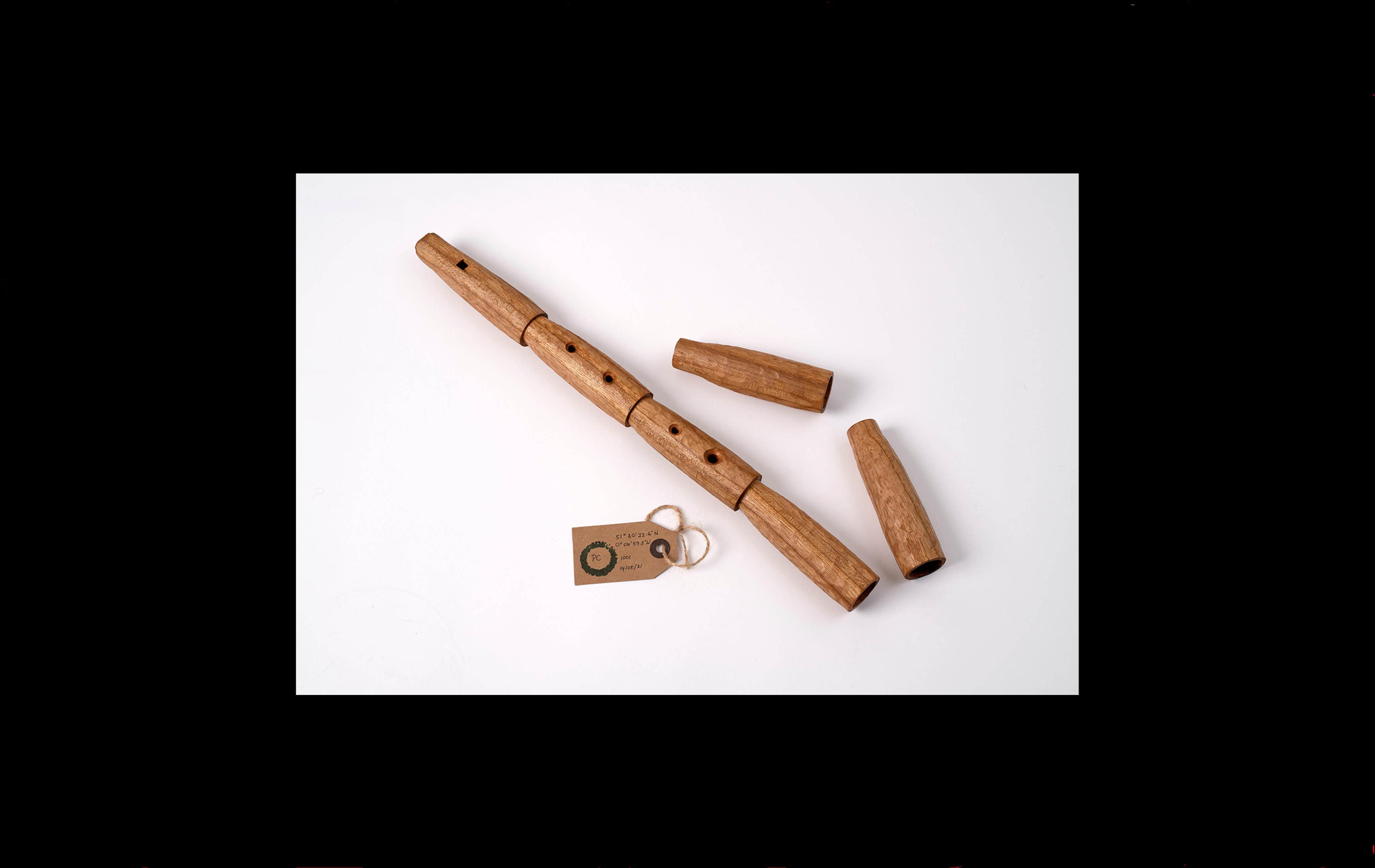

William ‘Mollitrappe’ Smythe, mole catcher

Moles have been the subject of much folklore down the years, much of it negative. Since medieval times they have been treated somewhere between loathing and pathological hatred. It’s true that they can cause damage to crops and embankments, but their reputation is perhaps more to do with their murky below-ground existence than their destructive actions.

By the 17th-century, people felt that nature should be controlled rather than simply managed. The New River Company cut a channel through the land to create a ‘new river’. Its soft banks needed to be protected from ‘the enemy beneath’, and so a mole catcher named William Smythe was employed.

It must have been a solitary life for William (who later changed his surname to ‘Mollitrape’, perhaps to cash in on the superstitious reputation of his trade). Trudging up and down the New River in all weathers, eyes darting from bank to bank scanning for the merest glimpse of a molehill.

Any ‘gentlemen in black velvet’ that William caught would have presented a lucrative opportunity. Moleskin or paws (which were often worn as good luck charms) could be sold. If a buyer for skins couldn’t be found, it is likely that he would have made his own moleskin coat.

COPSEY AND CREWE NARRATIVE EXCAVATION SERVICES™ are dedicated professionals with years of experience. They work to identify stories with an uncanny sense of time. By following unlikely tangents, their field work involves getting deep, looking underneath, behind and in the margins of things. They find curious metaphors and gaps in recorded knowledge.

Copsey and Crewe admit their findings are fictional and that they “aren’t archaeologists or anything”. The authentic stories they excavate are carefully selected from an array of infinite historic possibilities. Their selections remind us that histories aren’t fixed, they are interpreted from the here and now.

Copsey and Crewe’s current research is centred on unexcavated sites at New River Head and the banks of the New River.

With thanks to other experts in the field:

Alice Blackstock (artist), Alex Copsey (archaeologist), Michael Cranny and Denise Hickey (therapeutic services), Edwin and Wally (concierges at the Metropolitan Water Board building), James Holcombe (Erehwon Lab), Richard Marshall (Hermitage Brewery), Carol Partridge (straw weaver), Tom Rochester (bike mechanic), Andrew Smith (engineer and New River expert), Emily Stapleton-Jefferis (ceramicist) and the staff at Islington Local History Centre and Islington Museum.

This work was created as part of a residency project by Laura Copsey and Philip Crewe. In 2021 they researched the history of water in Clerkenwell. They focused on the trades and superstitions that were part of people’s lives in the 17th century.

Laura and Philip found the names of three working-class Londoners: Mary Woolastone, Joan Starkey and William Mollitrape. They crafted objects to tell each of their stories using different techniques and materials found at New River Head. They collaborated with a range of people, including Alice Blackstock (who made the Monmouth cap), Emily Stapleton-Jefferis (who advised on the water tankard) and Carol Partridge (who supported the making of Black Mary’s mummers mask and the wicker scold’s bridle).

New River Folk speculates on the experiences and beliefs of people who do not appear in ‘official’ museums or written histories. By combining archival fragments and fiction, Laura and Philip aim to make them visible.

Laura Copsey is an experimental illustrator from East Anglia and Philip Crewe is a designer from the Isle of Wight. They are a collaborative duo with a playful approach to illustration and storytelling. Their work is inspired by archaeological fieldwork and explores traces of human endeavour from history, heritage locations, traditional trades and museum collections. Laura and Philip inhabit the the grey area between what is real and imagined using processes that connect them to time and place, to communicate their experience and the narratives they excavate.

Images © Laura Copsey and Philip Crewe, photographed by Justin PipergerOur residency programme invites illustrators to explore heritage and is generously supported by the Barbara and Philip Denny Trust.